In 1990, as President O’Neil assumed the leadership of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression, John T. Casteen III was inaugurated seventh president of the University. He was the second longest-serving president after Edwin Alderman. In his long tenure, he presided over a diverse array of academic advancements in the spheres of teaching, students, infrastructure, and fundraising. Go to the President Emeritus page.

Funding Cuts

President Casteen came to the University after five years as president of the University of Connecticut. His experience at Connecticut, as an English professor at the University of California–Berkeley, and as Virginia’s secretary of education had acquainted him with the vagaries of public financing. Still, the funding cuts the University faced in the early nineties were dramatic, reductions in state support of 20 percent ($50 million) that threatened to cut the University off at its legs. All of these experiences led Mr. Casteen to believe that public universities in general and the University in particular need a certain amount of financial autonomy, free of the expensive and baroque financial cycling of University monies through the state’s cash drawers.

Fundraising and Financial Restructuring

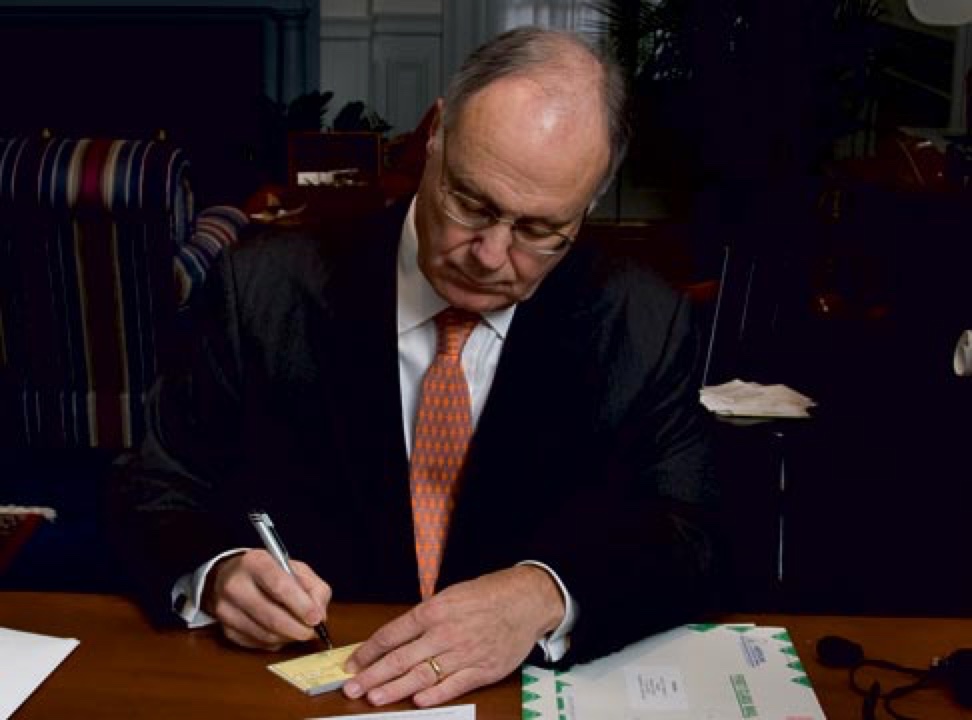

His fundraising and financial restructuring proved that the University could survive on permanently reduced state support, infusions of private support, and more efficiently managed money. Mr. Casteen’s first capital campaign, from 1994 to 2000, raised $1.43 billion.

On July 1, 2006, Virginia higher education formally entered a new fiscal arrangement with the state. The Restructured Higher Education Financial and Administrative Operations Act gave all sixteen of Virginia’s public colleges and universities new freedom from state control in areas such as spending, tuition, and personnel management, while requiring the schools to meet specific goals set by the state.

With more control of its financial resources, Mr. Casteen reasoned, the University would be able to thrive when the state has to deal with budget shortfalls. In his second capital campaign, Mr. Casteen and his administrative team had raised nearly $3 billion by the time he left office in 2010.

His fundraising was a great boon to the University’s endowment. In 1990, the market value of the endowment fund was $488 million. As of December 31, 2007, the market value of the consolidated endowment was $5.1 billion, impressive growth for any university endowment, especially so for a public one.

Fundraising and restructuring serve the universal purpose of the public academy and the more specific purpose envisioned by Thomas Jefferson. President Casteen wrote:

"This campaign’s purpose is to ensure that excellence thrives in public higher education, and specifically in this place where the concept of knowledge as the foundation for human freedom first took root in our hemisphere. Through this effort, we will generate, for our era and the next, that useful knowledge that matters most to our culture and our economy. We will focus on our most important product: women and men of uncommon achievement; honorable, responsible, intellectually powerful, and broadly knowledgeable citizens ready for effective engagement in public life—for the power and happiness that Jefferson saw as the benefits bestowed by the mastery of useful knowledge."

Representing the Larger World

Mr. Casteen’s emphasis on students was apparent in various ways. AccessUVa, a program that ensures loan-free funding of low income students’ educations, came into existence in 2003. To guarantee that the University is representative of the larger world that surrounds it, he instituted a new office, vice president for diversity and equity.

In representation of women and African Americans, the University’s faculty reflects positive change in this area. Among the sixty-one schools in the Association of American Universities, the University of Virginia moved from fifty-eighth to forty-eighth place for women, and from twenty-first to twelfth place for African Americans.

Broadening Horizons

Broadening the intellectual and cultural horizons of University of Virginia students were residential colleges, language houses, university seminars for first-year students, and expanded study abroad opportunities (in Bahamas, Belize, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, France, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Morocco, Peru, South Africa, Spain, Tibet, and the United Kingdom), new programs in media studies, materials science, and computer studies.

New Buildings

Resources for students and postgraduate scholars were especially evident in new buildings: the Harrison Institute and Small Special Collections Library, the South Lawn Phase I Project (which added over 100,000 square feet of academic space and is now home to history, politics, and religious studies), Wilsdorf Hall (housing the materials science department), and a building for the School of Education. Four Stanford White buildings have been refurbished—Cabell, Cocke, Garrett, and Rouss Halls, and John Kevan Peebles’s Fayerweather Hall (originally Fayerweather Gymnasium). Three modern-day athletic facilities were built during President Casteen’s administration: the Aquatics and Fitness Center, the John Paul Jones Arena, and an enlarged Scott Stadium at the Carl Smith Center.

Creation of Knowledge

As academic presidents have understood, to build an intellectual enterprise that supports life-advancing scholarship, a university has first to build for the creation of knowledge in laboratories, libraries, and classrooms.

Notably, in 2008, five medical research buildings were under construction: the Sheridan G. Snyder Translational Research Building, the Life Sciences Annex, the Carter-Harrison Research Building, the Claude Moore Medical Education Building, and the Ivy Translational Research Building.

A new building for Nursing, like many of the University’s building projects during Mr. Casteen’s administration, was financed with money raised in the course of two capital campaigns.

New Academic Programs

To accommodate growth and changes in knowledge and in the professions, a great number of new academic programs were created under the Casteen administration. The more than twenty new degree programs, not to mention a great number of programs in “concentrations,” included master of arts programs in bioethics, digital humanities, and public policy, and a joint Architecture /Art History Ph.D. program in the history of art and architecture.

The School of Continuing and Professional Studies implemented the very successful bachelor of interdisciplinary studies degree for nontraditional aged students. Engineering introduced a new bachelor of science degree in biomedical engineering and a new doctoral program in experimental pathology.

A university must not only accommodate the life of the mind, it must also enable social life. It does so by offering pastimes like football, theater, and music. Many millions of public and private dollars go into building the vast infrastructure required for so complex a community. At the University of Virginia, many of these dollars were raised at Carr’s Hill.

Business Use of Carr’s Hill

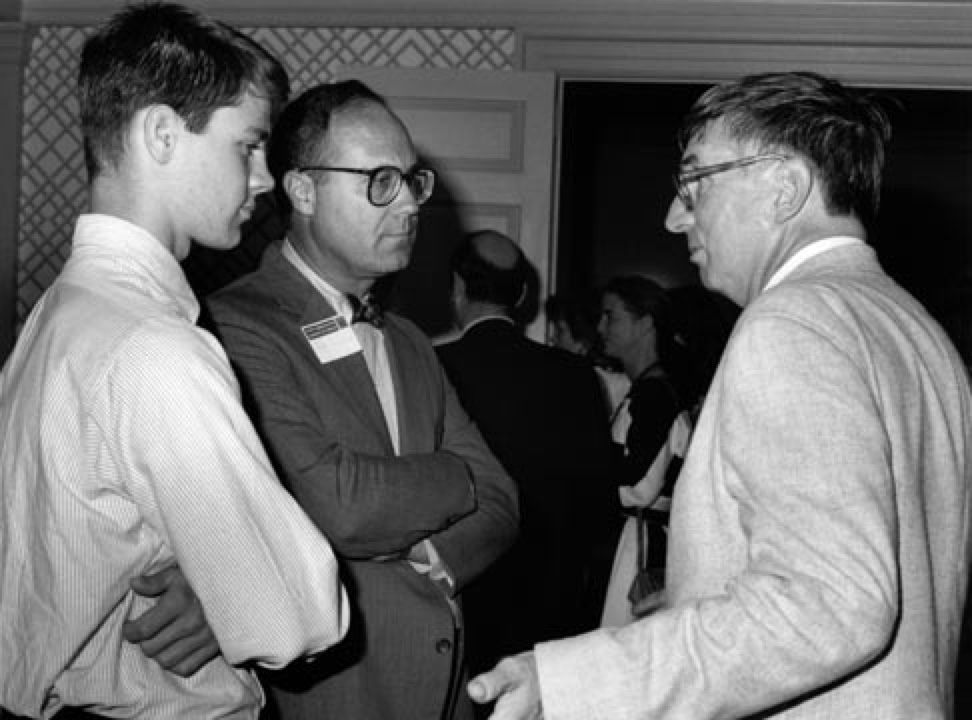

When Mr. Casteen and his former wife Lotta Lofgren moved to Carr’s Hill with their young children, Elizabeth and Lars, they had a sense of the developing role of the house in the University’s financial future. Mr. Hereford had begun to use the house the way the Aldermans first envisioned it. Mr. Casteen called the business use of the president’s house “the function of the official residence.”

As a place of residence and as a place for University business, President Casteen said, “I like the house very well. McKim, Mead & White had a feel for what makes a house comfortable. In Carr’s Hill, they created spaces far more livable for families than the rooms in Mr. Jefferson’s pavilions.” It also was the place for family occasions both great and small.

In 2003, Mr. Casteen married Elizabeth Taylor Foote. Theirs was the first wedding of a University president to take place in the president’s house. The large front hall of Carr’s Hill was the location of the ceremony. Family and friends watched as a bagpiper led Mr. Casteen from the living room into the front hallway to meet Mrs. Casteen and her four bridesmaids and flower girl as they walked down the long McKim, Mead & White staircase.

After the wedding and reception, the newlyweds drove off to honeymoon with their five children—John, Elizabeth, Lars, Alexandra, and Lily—their daughter-in-law Laurie Casteen, and their granddaughter Lily Casteen, as well as President Casteen’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. John Casteen Jr., and Mrs. Casteen’s brother, Geoffrey Taylor, his wife, Debby Delafield, and their daughter and son.

Betsy Casteen

Betsy Casteen, a former city planner elected to public office, brought her talents and experience to bear on the management of Carr’s Hill. She was the first president’s wife to have an office, in the guest house behind the president’s house, which helped her coordinate official University activities that took place under the aegis of the President’s Office. “I needed an office close to the house, but away from the activity. I leave my office door open and look out at the kitchen garden. Occasionally a dog or cat wanders in for a visit.”

Public Gathering

During the Casteen administration, the house was frequently used as a place of public gathering. In 2006–2007, 13,224 guests attended 104 events at Carr’s Hill, while overnight guests stayed at Carr’s Hill a total of 63 nights. About her role as Carr’s Hill hostess, Mrs. Casteen noted, “I love what I do. I like greeting people and trying to make them feel welcome. Many people are in awe of Carr’s Hill and surprised to find that we really live there. Many alumni are thrilled to see the house that they never before had entered.”

With students at play and at work all around the house, Mrs. Casteen noted that living on Carr’s Hill was “like living on the Lawn.” Like the faculty members and students who live in the historic buildings along the Colonnades, Mrs. Casteen realized that at Carr’s Hill she had a historical responsibility. “At Carr’s Hill, you are a kind of curator of the past,” she said. With students and visitors lounging in the gardens, strolling around the house’s perimeter, and sometimes peering in the windows, the family arranged for pockets of privacy on weekends and holidays at their private house in Albemarle. On the other hand, life in Carr’s Hill could be very exciting. “I love getting back into the swing of things in late August as the students are returning to Grounds. There is excitement in the air,” Mrs. Casteen said.